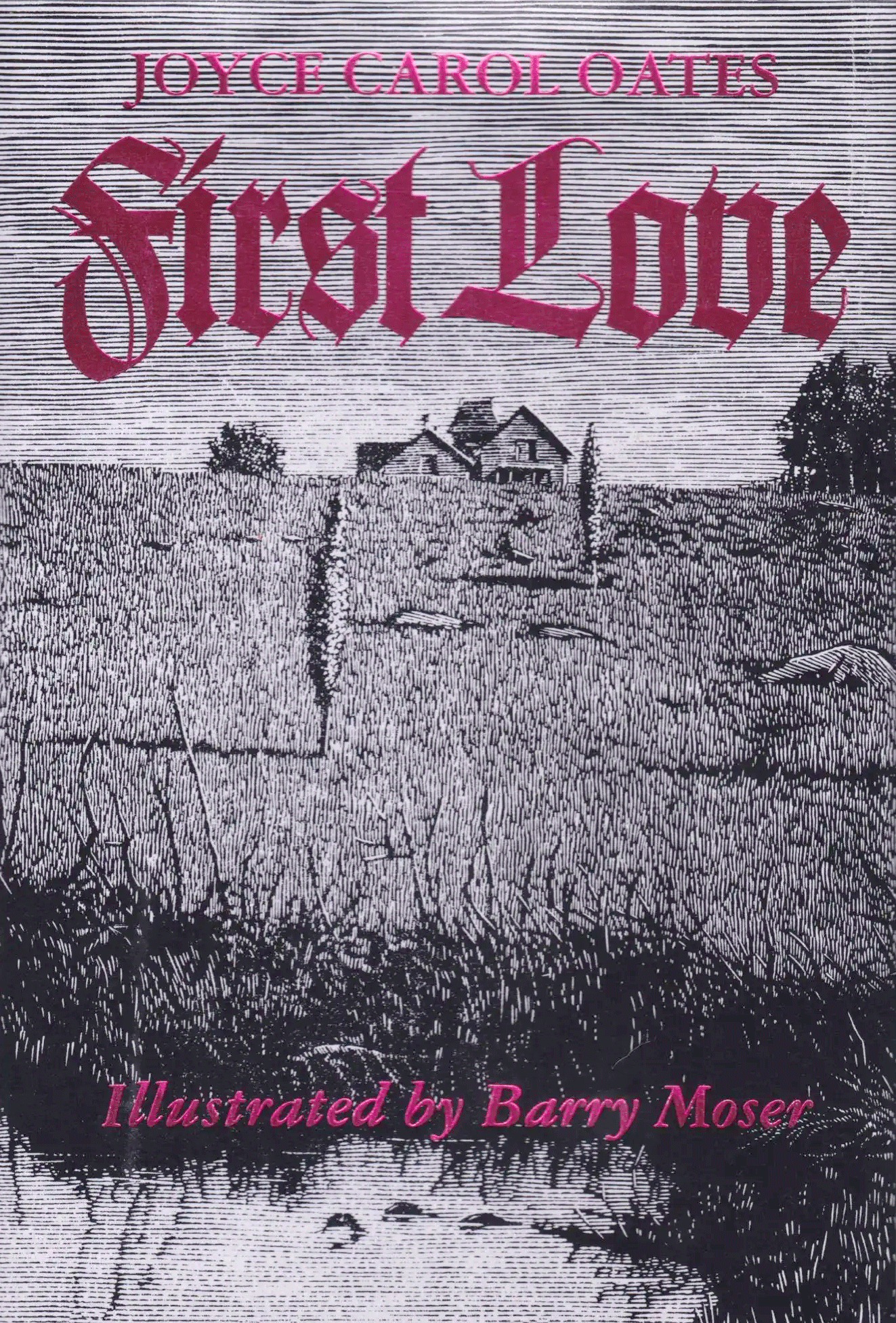

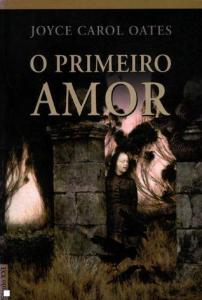

By Joyce Carol Oates

Designed and Illustrated by Barry Moser

Hopewell, NJ: Ecco Press, 1996

90 Pages

Josie S___ has come with her mother Delia to live in her great-aunt Esther Burkhardt’s house in upstate New York. Also living there is Josie’s cousin, Jared, Jr., on leave from the Presbyterian seminary. Preoccupied with his studies, impeccably dressed in his starched white shirts, distant and mysterious, Jared, Jr., is an intriguing figure to Josie’s curious and impressionable young mind. One summer afternoon, when Josie encounters Jared, Jr., at the riverbank behind the Burkhardt house, dark secrets are shared between them as an unnatural love blooms.

Josie S___ has come with her mother Delia to live in her great-aunt Esther Burkhardt’s house in upstate New York. Also living there is Josie’s cousin, Jared, Jr., on leave from the Presbyterian seminary. Preoccupied with his studies, impeccably dressed in his starched white shirts, distant and mysterious, Jared, Jr., is an intriguing figure to Josie’s curious and impressionable young mind. One summer afternoon, when Josie encounters Jared, Jr., at the riverbank behind the Burkhardt house, dark secrets are shared between them as an unnatural love blooms.

A moody sense of foreboding grips the reader from page one as religion, whispers of dark family secrets, violations of trust and virginity, bad blood, and a hint of incest all haunt the landscape of this startling tale of divided family loyalties, psychological manipulation, and the tangled strands of love and fear in the mind of a young girl groping for her way in one fractured American family.

Barry Moser’s beautifully haunting woodcuts enhance the general sense of unease in this novel, and Joyce Carol Oates once again proves herself a master storyteller as she plunges into the mind of a confused girl in this disturbing tale of twentieth-century gothic Americana.

Excerpt

Excerpt

The black snake. Feel yourself drawn! Behind the tall house bearing shingles the color of pewter. Into the heat-shimmering marsh below, sloping to the Cassadaga River. Your first morning in Ransomville, you slip from your hard, unfamiliar bed, dress swiftly, and leave the house wanting to see the river close up. Sun on your forehead light as a warning slap, already it’s hot before 8 A.M. Run, run!—feet sinking on the spongy earth. A fierce excited din of birds, bullfrogs, cicadas on all sides. At the bottom of the hill someone has laid planks down, into the marsh; you wonder if it’s safe to walk on them, they’re so rotted.

Fear is good, fear is normal. Fear will save your life.

Who has told you this, which adult, your mother, your father—or will it be Jared, Jr., to come?

Who has told you this, which adult, your mother, your father—or will it be Jared, Jr., to come?

Through a straggly stand of polelike barkless trees, you will learn are bamboo, the river shines bottle-green in the morning sun. Reflecting light like shattered glass. Which way is the river flowing, which way is north? North to Lake Oriskany? Hundreds of miles away.

On the farther shore of the river there’s a gauzy mist. The backs of houses and buildings nearly obscured by trees, junglelike vegetation. You enter the marsh shyly, a strange sensation like floating walking on the planks; the marsh is living, the dark rich damp soil makes an oozing, bubbling sound. The Cassadaga is a beautiful river, your mother has said. We’ll be there, looking out onto it.

From your mother you will inherit the belief that you can journey to your fate, there’s a place to be located on a map that’s destiny. If only you can get there. If only it isn’t too late. If no one stops you.

Just inside the marsh, where some of the cattails, reeds, bamboo stalks tower over your head, you see it—something black moving swiftly and sinuously. Gleaming-glittering along its length, S-shaped, oily-black. A snake! Long as your arm! You have an impression of an angry uplifted spade-shaped head, glaring-yellow eyes. It slithers across the very plank you’re standing on, three feet away, you’re paralyzed, staring, too frightened to scream. Many times you’ve seen garter snakes, grass snakes they’re called, but this snake!—its terrible eyes fixed upon you.

An instant later, it’s gone.

Already you’ve turned, panicked, running away. A flurry of gnats in your face and you wave wildly at them, “Oh! oh!”—blind and desperate as a small child running back up the hill, it’s a considerable hill, to your great-aunt’s house; the house so new to you you’ve never seen it before from this perspective, weatherworn and shabby with a look of anger, resentment like all such houses that yet maintain their dignity and some measure of pretension from the street, and you’re as disoriented as when you wake from a disturbing dream into a secondary dream, not knowing where you are, surrendering to pure emotion, and by the time, breathless, sweating, you’re at the house, your mother has come outside to catch you in her arms. “What on earth, Josie? What’s wrong with you?” Mother asks, and you tell her the snake, a long black snake, measuring with your tremulous arms the length of the snake, at least three feet long, and it seemed to be looking at you, as if you knew you, and Mother laughs, brushing at your uncombed hair with a cool hand, “Yes? Really?”

Your great-aunt Esther Allan Burkhardt, whose house this is, and whom you’d never seen before the previous day, has come to stand in a doorway, frowning at you and Mother, arms wrapped in her apron. White as flour the apron, and her round rimless emotionless eyeglasses winking in the sun

“That’d be a garter snake,” the old woman says flatly. “They don’t grow beyond ten or twelve inches and they’re not dangerous that I ever heard of. You keep to yourself, miss, and they keep to themselves.”

Book Covers

Interview

Interview

Courtesy of Ecco Press

Q: What was your inspiration for FIRST LOVE?

A: FIRST LOVE began as more of a straight, realistic story about a young girl who, with her divorced mother, comes to live with distant relatives in upstate New York. Among the family is a young man accused, though never convicted, of child molestation. The family doesn’t tell the girl or her mother about the young man’s past—and the girl becomes his victim.

For two or three years, I had this idea for a novella. I wanted to present it from the girl’s point of view, in retrospect. I began to meditate on the bond that often develops between victim and abuser, and FIRST LOVE evolved.

Q: You describe FIRST LOVE as a Gothic romance. Can you explain?

A: FIRST LOVE is a Gothic romance because it deals with taboo subjects: a child’s romantic yearning for a relationship with a young man; a victim’s enchantment with and devotion to an abuser. Such emotions are complicated—and they make people very uncomfortable. And the setting comes from the Gothic tradition: an isolated, forbidding house with family secrets.

Q: FIRST LOVE deals with many social themes: child abuse, sexual obsession, psychological manipulation, broken families. Can you discuss?

Q: FIRST LOVE deals with many social themes: child abuse, sexual obsession, psychological manipulation, broken families. Can you discuss?

A: It’s hard to talk about a work of literature in that way. There’s a danger of becoming reductionist. A work of literature is its language, mood, atmosphere. It’s not just about an issue.

Q: Your protagonist, Josie S__, is an 11-year-old wise beyond her years, who at times seems to seek out abuse at the hands of her 25-year-old cousin, Jared, Jr. What motivates her?

A: I believe there’s a strong element of masochism in most women. Josie is a young woman involved in, and fascinated by, her own degradation. She’s fascinated by the mystery of Jared, Jr., this imposing male. She’s also motherless and fatherless, desperate for attention, willing to be exploited. Look at members of cults, followers of David Koresh. People will endure much degradation for attention, for love.

Q: Why do you say Josie is “motherless”?

A: Josie’s mother doesn’t want to “play” mother, doesn’t want to be a mother. She’s a strong-willed woman of her own, and very narcissistic. She’s not a villian, but she’s not there for Josie. FIRST LOVE is about that too.

Q: FIRST LOVE’s real villain, Jared, Jr., is studying to become a Presbyterian minister. Would you call him a religious fanatic?

A: Jared, Jr., is fighting the demons of his own internal disbelief. He’s inherited a burden from his grandfather. Living in “The Reverand’s” house, he’s trying to live up to “The Reverand’s” name, “The Reverand’s” calling. Jared, Jr. is disturbed, weak and pathetic. But there’s no excuse for child abuse.

Q: FIRST LOVE is set in rural, upstate New York, which the Boston Herald has called the “nourishing heartland” of your best fiction. Is the inspiration for Ransomville taken from your birthplace, Lockport, New York?

A: Ransomville is a real place, not far from where my parents live. But the real Ransomville is nothing like the fictionalized setting of FIRST LOVE.

Reviews

Reviews

Kirkus Reviews, June 15, 1996, p850

Oates at her best—and a happy reminder that she remains one of our foremost chroniclers of childhood’s awakening and woman’s fate.

Publisher’s Weekly, June 24, 1996, p44

With her usual skill, Oates creates a claustrophobic atmosphere of festering evil. Through hints, forebodings and mythic symbols, her slim but hypnotic tale speaks volumes about the pain and helplessness of sexually abused children too frightened to speak out to uncomprehending adults. The power of this beautifully produced book is augmented by Moser’s eerie woodcuts, which crystallize the aura of menace.

Randy Souther, San Francisco Chronicle Book Review, August 4, 1996, p1

The story is told from the perspective of an adult Josie, but her narrative voice takes two distinct strains: one realistic and one gothic. The realistic voice narrates in the first person and tells most of the story; it is when Josie is enthralled by Jared Jr., however, that her gothic voice narrates in the second person, suggesting that she must distance herself. from such shattering experiences to be able to speak of them. … Oates is not known for writing happy endings, and she does not provide one here, but it is surprising, in light of her reputed “dark vision,” how many of her works do have positive endings, how many of her insulted and injured characters, like Josie, transcend their wrenching experiences.

Brad Hooper, Booklist, July, 1996, p1804

Oates’ latest book (“latest” for a few months at most, given her prolificacy) is a tightly written, brilliantly effective novella about a brief but consequential time in a girl’s life, which, like a coin, has two opposite sides: The person responsible for emblazoning the poignancy of first love on her heart is also the one taking advantage of her naive sexuality.

David Gates, New York Times Book Review, September 15, 1996, p11

There must be unjaded souls somewhere for whom the dark erotics of serpents and saviors, blood and bondage, will provide an eye-opening insight into something or other. But for those who’ve seen it all before, the truly scary character here is Josie’s mother, who’s left her husband for reasons she won’t tell, takes up with other men and, when not neglecting her daughter outright, gives her moments to remember like this: ”You’d followed her into the bedroom and there she stood waiting for you. ‘What is the meaning of ”Mother?” We all know that ”Mother” is warm, loving, forgiving, and not terribly bright. So let’s put ”Mother” here.’ She laid the article of clothing onto the bed, positioned the upper part of it against the pillow with a certain mordant tenderness.” (Yes, Ms. Oates has probably seen ”Psycho.”) In this story, the void between needy daughter and hopelessly remote mother is the true case study in child abuse.

Judith Wynn, Boston Herald, August 4, 1996, p57

In Oates’ dreamlike, utterly convincing world, the strong brutalize the weak simply because they can. And the weak? They succumb or they get strong and start hunting for prey of their own. No mere victim, Josie learns about willpower and choice. What she does with her newfound strengths makes “First Love” a weirdly beautiful gothic tale of survival and transcendence.

Lee Milano, Dallas Morning News, August 25, 1996, page 8J

Most readers will not need to be reminded of the gothic themes, imagery and tone that permeate this novel dark as winter afternoon. Ms. Oates, however, adds several artistic touches that give the book real depth, making it much more than a horror story.

Barbara Hoffert, Library Journal, August, 1996, p113

Enthralling and overwritten, psychologically acute and deftly tuned to contemporary writing trends, First Love is vintage Oates.

Paula Chin, People, August 26, 1996, p29

Moody and vivid, if not gripping, First Love is a little gothic romance with a bittersweet aftertaste. “You would not call it love,” Josie tells herself as spring comes. “You would have another name for it.”

Susan Salter Reynolds, Los Angeles Times Book Review, September 8, 1996, p11

A desperate story, and Joyce Carol Oates’ passages about the swamp, the primordial ooze that all this bad behavior climbs from, are lovely and more delicate than the plot, as are her animistic character descriptions: “The attentive grandson drove his grandmother to the clinic and left her and now on his skinny haunches scrambling backward, skittering against the hardwood floor of his bedroom.”

Carolyn Kelly, Austin American Statesman, August 25, 1996, page F7

Oates writes beautifully, making lovely descriptions: the river is “bottle-green,” an apron is “white as flour.” I can picture and understand the big, still house in New York filled with unwelcoming kinfolk. But many characters are never fully realized; there’s some sort of black snake analogy; and the mother speaks in fancy, inexplicable circles around her daughter. Amid all of this is a bizarre, violent relationship between Josie and the creepy cousin. I didn’t fall for “First Love.” Not even a slight crush.

Boston Globe, August 4, 1996, N, 15

Glamour, September 1996, p132

Detroit News, September 14, 1996, D26

Chicago Tribune, September 22, 1996, 14, 3

Image: Barry Moser

Image: Barry Moser

Josie S___ has come with her mother Delia to live in her great-aunt Esther Burkhardt’s house in upstate New York. Also living there is Josie’s cousin, Jared, Jr., on leave from the Presbyterian seminary. Preoccupied with his studies, impeccably dressed in his starched white shirts, distant and mysterious, Jared, Jr., is an intriguing figure to Josie’s curious and impressionable young mind. One summer afternoon, when Josie encounters Jared, Jr., at the riverbank behind the Burkhardt house, dark secrets are shared between them as an unnatural love blooms.

Josie S___ has come with her mother Delia to live in her great-aunt Esther Burkhardt’s house in upstate New York. Also living there is Josie’s cousin, Jared, Jr., on leave from the Presbyterian seminary. Preoccupied with his studies, impeccably dressed in his starched white shirts, distant and mysterious, Jared, Jr., is an intriguing figure to Josie’s curious and impressionable young mind. One summer afternoon, when Josie encounters Jared, Jr., at the riverbank behind the Burkhardt house, dark secrets are shared between them as an unnatural love blooms. Who has told you this, which adult, your mother, your father—or will it be Jared, Jr., to come?

Who has told you this, which adult, your mother, your father—or will it be Jared, Jr., to come?

Q: FIRST LOVE deals with many social themes: child abuse, sexual obsession, psychological manipulation, broken families. Can you discuss?

Q: FIRST LOVE deals with many social themes: child abuse, sexual obsession, psychological manipulation, broken families. Can you discuss? Reviews

Reviews Image: Barry Moser

Image: Barry Moser