By Joyce Carol Oates

New York: Ecco, 2013

669 Pages

A major historical novel from “one of the great artistic forces of our time” (The Nation)—an eerie, unforgettable story of possession, power, and loss in early-twentieth-century Princeton, a cultural crossroads of the powerful and the damned.

A major historical novel from “one of the great artistic forces of our time” (The Nation)—an eerie, unforgettable story of possession, power, and loss in early-twentieth-century Princeton, a cultural crossroads of the powerful and the damned.

Princeton, New Jersey, at the turn of the twentieth century: a tranquil place to raise a family, a genteel town for genteel souls. But something dark and dangerous lurks at the edges of the town, corrupting and infecting its residents. Vampires and ghosts haunt the dreams of the innocent. A powerful curse besets the elite families of Princeton; their daughters begin disappearing. A young bride on the verge of the altar is seduced and abducted by a dangerously compelling man–a shape-shifting, vaguely European prince who might just be the devil, and who spreads his curse upon a richly deserving community of white Anglo-Saxon privilege. And in the Pine Barrens that border the town, a lush and terrifying underworld opens up.

When the bride’s brother sets out against all odds to find her, his path will cross those of Princeton’s most formidable people, from Grover Cleveland, fresh out of his second term in the White House and retired to town for a quieter life, to soon-to-be commander in chief Woodrow Wilson, president of the university and a complex individual obsessed to the point of madness with his need to retain power; from the young Socialist idealist Upton Sinclair to his charismatic comrade Jack London, and the most famous writer of the era, Samuel Clemens/Mark Twain–all plagued by “accursed” visions.

An utterly fresh work from Oates, The Accursed marks new territory for the masterful writer. Narrated with her unmistakable psychological insight, it combines beautifully transporting historical detail with chilling supernatural elements to stunning effect.

Genre Series

Genre Series

“America as viewed through the prismatic lens of its most popular genres”

The novels in this series are written in the styles of genre fiction popular in the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and are “linked by political, cultural, and moral … themes, set in a long-ago / mythic America intended to suggest contemporary times.” Each book is the story of a family intersecting, variously, with America’s troubled history of the treatment of women and children, and its battles over race and class divisions. These concerns are frequently translated into Gothic story elements (to varying degrees, depending on the novel), which is why these books are sometimes referred to as the “Gothic Series,” or the “Gothic Saga,” or the “American Gothic Quintet” Though thematically linked, each novel tells an independent story.

The Novels of the Genre Series:

- Bellefleur (1980) — Genre: historical novel / family saga 1770s–1980s

- A Bloodsmoor Romance (1982) — Genre: historical novel / romance 1879–1899

- The Accursed (2013) — Genre: historical novel / gothic horror 1900–1910

- Mysteries of Winterthurn (1984) — Genre: historical novel / detective mystery 1880s–1910s

- My Heart Laid Bare (1998) — Genre: historical novel / con artists and confidence games 1909–1932

“The opportunity might not be granted me again, I thought, to create a highly complex structure in which individual novels (themselves complex in design, made up of ‘books’) functioned as chapters or units in an immense design: America as viewed through the prismatic lens of its most popular genres.” —Joyce Carol Oates, 1985

Contents

Contents

Map

Author’s Note

Prologue

Part One – DEMON BRIDEGROOM

Ash Wednesday Eve, 1905

Postscript: “Ash Wednesday Eve, 1905”

Narcissus

The Spectral Daughter

Angel Trumpet; Or, “Mr. Mayte of Virginia”

Author’s Note: Princeton Snobbery

The Unspeakable I

The Burning Girl

Author’s Note: The Historian’s Confession

The Spectral Wife

The Demon Bridegroom

Part Two – THE CURSE INCARNATE

The Duel

Postscript: The Historian’s Dilemma

The Unspeakable II

The Cruel Husband

The Search Cont’d

October 1905

“God’s Creation as Viewed from the Evolutionary Hypothesis”

The Phantom Lovers

The Turquoise-Marbled Book

The Bog Kingdom

Postscript: Archaeopteryx

The Curse Incarnate

Part Three – “THE BRAIN, WITHIN ITS GROOVE . . .”

“Voices”

Bluestocking Temptress

The Glass Owl

“Ratiocination Our Salvation”

The Ochre-Runnered Sleigh

“Snake Frenzy”

Postscript: Nature’s Burden

“Defeat at Charleston”

“My Precious Darling . . .”

“A Narrow Fellow in the Grass . . .”

Dr. Schuyler Skaats Wheeler’s Novelty Machine

Quatre Face

“Angel Trumpet” Elucidated

“Armageddon”

Part Four – THE CURSE EXORCISED

Cold Spring

21 May 1906

Lieutenant Bayard by Night

Postscript: On the Matter of the “Unspeakable” at Princeton

“Here Dwells Happiness”

The Nordic Soul

Terra Incognita I

Terra Incognita II

The Wheatsheaf Enigma I

The Wheatsheaf Enigma II

“Sole Living Heir of Nothingness”

The Temptation of Woodrow Wilson

Postscript: “The Second Battle of Princeton”

Dr. De Sweinitz’s Prescription

The Curse Exorcised

A Game of Draughts

The Death of Winslow Slade

“Revolution Is the Hour of Laughter”

The Crosswicks Miracle

Epilogue: The Covenant

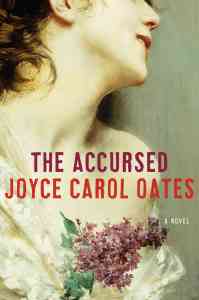

Book Covers

Working Title

Working Title

“The Crosswicks Horror”

Epigraphs

Epigraphs

“From an obscure little village we have become the capital of America.”

—Ashbel Green, Speaking of Princeton, New Jersey, 1783

“All diseases of Christians are to be ascribed to demons.”

—St. Augustine

Awards

Awards

- Shirley Jackson Awards, Novel finalist, 2013

- New York Times Notable Books of the Year, 2013

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The truths of Fiction reside in metaphor; but metaphor is here generated by History.

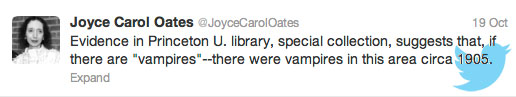

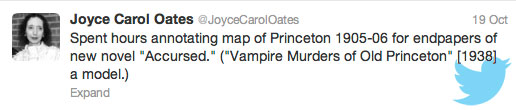

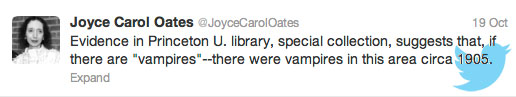

Tweets

Tweets are from October 19, 2012

Excerpt

Excerpt

It was at this moment that the young women made their discovery that Todd and Thor were nowhere in sight; though the boy’s shouts and laughter, and the dog’s wild barking, seemed to be echoing from all directions of the forest.

Annabel led the way deeper into the forest, calling her cousin’s name; then, faltering, she surrendered the lead to Willy, who led them in another direction, calling out: “Todd! You are very bad! Why are you hiding from us? Come out at once!”

After some stressful minutes, as the young women made their way ever more deeply into a soft, sinking, bog-like part of the forest, into which Stony Brook Creek evidently emptied, at last they sighted Todd at the same moment, in a sort of clearing, in which gigantic logs lay in a jumbled profusion; the logs being ossified, it seemed, and formidable as fallen monuments. The sunshine that fell slantwise into this open space, having taken the peculiar quality of the great forest, did not seem, somehow, a natural sunshine, or the light of the sun itself, but rather a queer, silvery, lunar effulgence, unsettling yet not entirely disagreeable.

After some stressful minutes, as the young women made their way ever more deeply into a soft, sinking, bog-like part of the forest, into which Stony Brook Creek evidently emptied, at last they sighted Todd at the same moment, in a sort of clearing, in which gigantic logs lay in a jumbled profusion; the logs being ossified, it seemed, and formidable as fallen monuments. The sunshine that fell slantwise into this open space, having taken the peculiar quality of the great forest, did not seem, somehow, a natural sunshine, or the light of the sun itself, but rather a queer, silvery, lunar effulgence, unsettling yet not entirely disagreeable.

There Todd stood, his head lowered, and his wild dark hair rising in tufts above his pallid face; but though both Annabel and Willy called to him, he seemed not to hear; nor did Thor leap up from the lichen-bed in which he lay, to approach them with his tail wagging, in his usual manner.

The young women then noticed that Todd was not alone in this strange space: but there stood before him, engaging him in earnest conversation, a young girl unknown to either Annabel or Willy, of slender proportions, indeed wraith-like, with long and unruly dark hair, and a round, dusky-skinned, sharp-boned face; and dark eyes that seemed to blaze with passion. The girl was very coarsely dressed in what appeared to be work-clothes, that had been badly soiled, torn, or even burnt. The fingers of her right hand appeared to be misshapen, or mangled. Most remarkably, small flames lightly pulsed about the girl: now lifting from her untidy hair, now from her tensed shoulders, now from her outstretched hand!—for the girl was reaching out to Todd, as if to grasp his hand.

More remarkably still, around the girl’s neck was a coarse rope, fashioned into a noose; the length of the rope about twelve feet, and its end blackened as from a fire.

And ah!—how the girl’s topaz eyes blazed, with vehemence!

Was the hellish vision a trick of the sunlight? Did Annabel’s and Wilhelmina’s widened eyes deceive them? The flames pulsed about the girl, and rippled, and subsided; and flared up again, lewdly vibrating, tinged with blue like a gas-jet, at their core; so subtle, in hellish beauty, they might have been optical illusions, or mirages, caused by some fluke of the fading light.

“Todd! Come here …”

In a faltering voice Annabel called to him, but Todd gave no sign of hearing.

For it seemed that Todd had fallen under the spell of the demon girl and could not rouse himself to flee from her, as if not comprehending what the pulsing blue flames might mean, or the coarse rope around her neck; or the danger to him, as she came very close to touching him, caressing him, with her burning fingers, and he did not shrink away.

“Todd! It’s Annabel—Annabel and Wilhelmina—come to take you home. Todd!”

Yet, was the burning girl not most mesmerizing?—though dusky-skinned, with a flat, slightly thick nose, and thick lips, and unruly and unwashed-looking hair tumbling down her back; and those uncanny luminous eyes; and the noose around her neck, that must have been uncomfortable, for it seemed tight enough to constrict breathing…It might have been that Todd believed the girl to be his own age, yet a closer look suggested that she was considerably older, at least the age of Annabel or Wilhelmina, a young woman and not a girl.

And there was the German shepherd Thor so strangely stretched on the lichen-bed a few yards from the feet of the burning girl, muzzle extended, ears pricked into little triangles, eyes adoringly fixed upon the girl—why was Thor not barking but only just panting, audibly, as if he had run a great distance to throw himself down, as if in worship?

And there was the German shepherd Thor so strangely stretched on the lichen-bed a few yards from the feet of the burning girl, muzzle extended, ears pricked into little triangles, eyes adoringly fixed upon the girl—why was Thor not barking but only just panting, audibly, as if he had run a great distance to throw himself down, as if in worship?

When Annabel and Willy, clutching hands, ran forward, with little shrieks of concern, the burning girl turned to them, with an expression of rage, dismay, and anguish; now, a paroxysm of flames whipped over her figure, to obliterate her entirely; and, in the blink of an eye, as if she had never been, the burning girl vanished.

“Todd! Thank God, you are unharmed!”—so Annabel cried, rushing to Todd, to embrace him; and quite shocked, when Todd wrenched himself from her, and fixed upon her a look of angry contempt.

“Here is Cousin Annabel,” Todd began to chant, in the singsong that so maddened his father, “who has come too soon; here is Miss Willy, who has come unbidden; here is Todd, who had at last found a friend in the forest, but who has lost his friend—poor silly Todd, left all alone.”

Most alarmingly, the German shepherd, who had known Annabel since he was a puppy, and had known Wilhelmina Burr nearly that long, had leapt to his feet and was growling deep in his throat, ears laid back and hackles raised, and formidable teeth exposed as if—(could this be possible?)—he failed to recognize the distraught young fair-haired woman and her dark-haired friend.

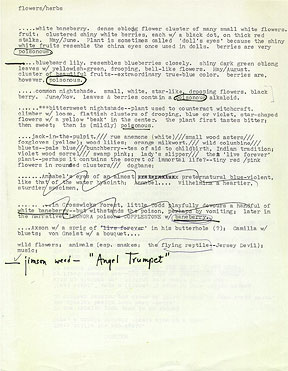

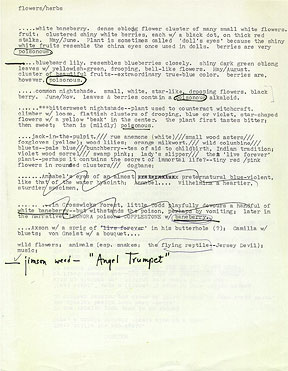

Manuscript Images

Manuscript Images

All manuscript images are in pdf format. Images may not be reproduced without permission of Joyce Carol Oates.

A scary scene, complete, in its way, on two sides of an envelope, side 1.

Scary scene on evelope, side 2.

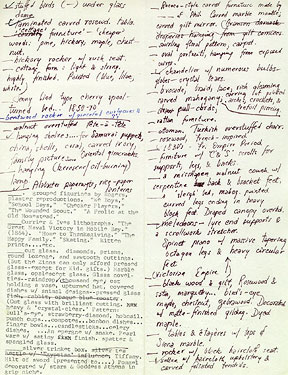

Lists of flowers and herbs for possible use in the novel.

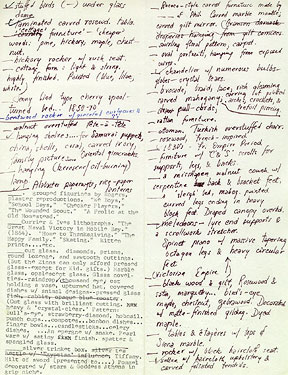

Lists of furnishings for possible use in the novel.

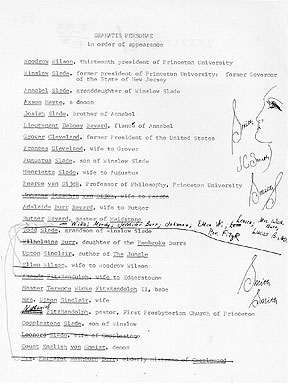

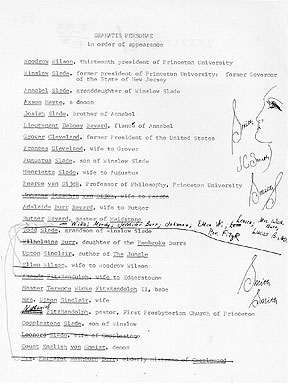

Dramatis Personae.

Dramatis Personae (continued).

More manuscript Images

Matthew Surridge on The Accursed

Matthew Surridge on The Accursed

Matthew David Surridge, Black Gate: Adventures in Fantasy Literature, June 8, 2013

As a theme, it all fits with the genre tradition of the gothic: with the idea of truly unspeakable horrors. With things that cannot be said directly. From a certain point of view, this is a drama of repression, of hidden things whose existence is too fearsome to admit forcing their way to the surface. One could argue, I think, that the historian-narrator’s whole constructed story is actually a sophisticated attempt on his part to deny certain key truths behind his own birth — a kind of Oedipal agon, rewriting and murdering his own father. But more than that, there’s something universal, something comprehensive, about the gothicism and the curses of the book: it involves and implicates not only personal stories, but American society as a whole, politics and religion and art, past and future. The book’s a Menippean satire, or, in Northrop Frye’s term, an anatomy: an appropriately ghoulish image.

Which is not to say that it neglects the romantic and supernatural. It’s filled with event and wonder: vampires, demons, ghosts, the Jersey Devil. It just so happens that it may be possible to read the book in such a way as to suggest that these things are deceits or hallucinations. As I’ve said, mirrors are a significant image in the book, along with twinning and dopplegangers; the book seems to be a duplicate of itself, both supernatural romance and ironic satire. The Gothic tradition is evoked, but so is the Greek. Both unite to form the whole story, which may be the point — dualities (as white with black) are illusory, products of vision. Purity’s a myth.

Read the full review

Reviews

Reviews

Publishers Weekly, November 5, 2012

“Oates has published more than enough books to take risks, and her newest is exactly that: first drafted in the early 1980s, then set aside, the novel is, in addition to being a thrilling tale in the best gothic tradition, a lesson in master craftsmanship …. The story sprawls, reaches, demands, tears, and shrieks in homage to the traditional gothic, yet with fresh, surprising twists and turns. Oates weaves historical figures throughout, grounding the narrative in a quasi-familiar reality without losing a “through the looking-glass” surrealism. The cause of the curse is not much of a surprise, but the way it’s broken is both traditionally mythic and satisfying. Oates has given us a brilliantly crafted work that refreshes the overworked tradition. The author’s rage at social injustices and the horrific “cures” for invalids boil beneath the surface; she’s skilled enough to let them fuel the fury without erupting into fire. Take on this 700-page behemoth with an open mind, and hang on for the ride.”

Donna Seaman, Booklist, December 15, 2012, p. 23

“… a lush, arch, and blistering fusion of historical fact, supernatural mystery, and devilish social commentary…. readers will be bewitched by a fantastically dramatic, supremely imaginative plot rife with ghosts, vampires, demons, and human folly. Oates brings her nightshade humor and extraordinary fluency in eroticism and violence, American history and literature (her magnetizing characters include Mark Twain, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair) to this piercing novel of the devastating toll of repression and prejudice, sexism and class warfare. A diabolically enthralling and subversive literary mash-up.”

Kirkus Reviews, January 15, 2013

“Oates finishes up a big novel begun years before—and it’s a keeper…. The Curse is the one of past crimes meeting the future, perhaps; it is as much psychological as real, though Oates takes pains to invest plenty of reality in it. Carefully and densely plotted, chockablock with twists and turns and fleeting characters, her novel offers a satisfying modern rejoinder to the best of M.R. James—and perhaps even Henry James. Though it requires some work and has a wintry feel to it, it’s oddly entertaining, as a good supernatural yarn should be.”

Pamela Miller, StarTribune, March 2, 2013

“The plot is like the worst, longest, most incoherent nightmare you ever had. And yet, it’s brilliant. Oates’ writing shines in every line, capturing the era’s florid narrative and vocal styles…. Whatever you take away from this novel, it’s a bedazzling intellectual ride.”

Ron Charles, Washington Post Book World, March 5, 2013

“…it’s spectacular — a coalescence of history, horror and social satire that whirls around for almost 700 mesmerizing pages. Oates started the novel in 1984 but set it aside to steep in its own febrile juices for three decades. Now “The Accursed” arises in full bloom, boasting as much craft as witchcraft…. With its vast scope, its mingling of comic and tragic tones, its omnivorous gorging on American literature, and especially its complex reflection on the major themes of our history, “The Accursed” is the kind of outrageous masterpiece only Joyce Carol Oates could create.”

A.J. Kirby, New York Journal of Books, March 5, 2013

“The Accursed is a unique, vast multilayered narrative; a genre bending beast of a book, utterly startling from start to finish, compulsive and engaging, the writing crackling with energy and wit.”

Deborah Harkness, National Public Radio, March 5, 2013

“… a grand literary pastiche in style and substance … this supernatural tale becomes a meditation on the perils of parochial thinking. It demands we think—with monsters—about our failure to face the darkest truths about ourselves and the choices we’ve made.”

Carol Memmott, USA Today, March 13, 2013

“There are no better scenes of Gothic horror than those Oates weaves into this brilliant work.”

Stephen King, New York Times Book Review, March 17, 2013, p.1

“Joyce Carol Oates has written what may be the world’s first postmodern Gothic novel: E. L. Doctorow’s ‘Ragtime’ set in Dracula’s castle. It’s dense, challenging, problematic, horrifying, funny, prolix and full of crazy people. You should read it. I wish I could tell you more.”

Wendy Smith, Los Angeles Times, March 31, 2013, p. E13

“Dostoevsky is the only other novelist who comes to mind as capable of creating the lacerating confession phrased in majestic biblical cadences that Oates delivers here. Her scarifying vision of divine order and its bitter earthly consequences recalls his famous ‘Grand Inquisitor’ scene, with a sharper political edge. It’s the mark of artistry grown ever more assured over the course of Oates’ 50-year career that this metaphysical outburst flows naturally from the unnerving parade of ghastly events that precedes it. ‘The Accursed’ triumphantly fulfills its gothic mandate to make our skin crawl, but it also accomplishes the much more difficult task of frightening us with its ideas.”

Barbara Hoffert, Library Journal, November 15, 2012

“… a smart and relentlessly absorbing read.”

Jill Korber, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 3, 2013

“… a genuinely frightening mystery with poetic, masterful language…”

Gabriel Murray, Strange Horizons, April 1, 2013

“… an odd and fascinating beast of a novel…”

Francine Prose, The New York Review of Books, April 25, 2013

“… Oates has invented an entirely new fictional category by combining several familiar popular genres: The Accursed is a gothic-academic-historic novel of ideas. … Ultimately, the pyrotechnical quality of Oates’s imagination is what keeps us reading with pleasure…”

Robert L. Kehoe III, First Things, August 23, 2013

While some have cast The Accursed as a simple, though entertaining, Gothic story, such a claim does a disservice to the tangled roots of family, culture, history and theological idiosyncrasy Oates untangles. As a novel it is a remarkable study of human nature and a persuasive challenge to Duns Scotus’ postulation that evil is something “about which the most learned and ingenious . . . can know almost nothing.”

Monique Polak, National Post, March 15, 2013

Rabies and Race: An Hypothesis

Rabies and Race: An Hypothesis

Outtake from an early version of the novel. Originally published in Partisan Review, 1983

HEREWITH, an account of the somewhat controversial Fuerst hypothesis, first presented as a lecture at Princeton, in the autumn of ’98, by that esteemed gentleman of science Dr. Palmer Fuerst,—whose numerous books and monographs, I am puzzled to note, are no longer to be found on the shelves of the University library.

At this time, Dr. Fuerst held the position of President, of the American Philosophical Society, and was Director of the Boston Foundation for Scientific Inquiries, having served, for upward of twenty years, on the science faculty at Harvard. (‘Tis my good fortune that a monograph of “Rabies and Race” is yet to be found, in one of our rural libraries here in the Hopewell Valley,—else I should be hard pressed to discover, and to recount, the particulars of Dr. Fuerst’s provocative message!) That he was invited by his colleagues at Princeton, to address the student body, and the community in general, testifies, I think, to a commendable lack of rivalrous or bitter feelings, betwixt the two great universities,—albeit that the youthful athletes of Harvard and Princeton may have felt somewhat differently, owing to a fiercely played football match of the previous season, when Harvard, as it were, “trounced” Princeton, in a game thought by numerous disinterested parties, to be unfair.

Since the Boston Foundation for Scientific Inquiries, which undertook the series of experiments, of which Dr. Fuerst so eloquently spake, was funded, I think wholly, by that august organization, the Sons of America Protective Association, to which numerous of our Princeton families either belonged, or contributed, it cannot, I think, be seriously claimed, that the Princetonians were o’er-conservative in their distrust of Science; or opposed, in any absolute way, to scientific research and experimentation. (Provided, of course, that it did not violate certain bounds of common decency,—the which the shrill-voiced female suffragists* daily transgressed, in those years, with their shameless public clamor for contraceptive devices, abortion, and even “free” love—!) When the revered Dr. Charles Hodge, head of the Princeton Theological Seminary, made the proud statement for which he is known to this day, as to his fearlessness, in declaring that a “new idea had never originated in his seminary, ” he was addressing himself to the Science of Theology, and not to the Science of Man; for the devout old soul conceived of Theology as an orderly statement of what the Holy Book says,—and not what hot-headed young fools think it means.This seems to me reasonable enough, for the Seminary was, in those tumultuous years, engaged in grave warfare, with the notorious liberals of the Union Theological Seminary; and had to guard itself against unprovok’d attacks, by those theologians who fancied “Biblical criticism,”—and wished to enforce unneeded reforms, upon the Presbyterian Church. (Nay, it is very unlikely, that any fair-minded person would believe the Seminary to have been in error, in its pursuit of divers heresy and blasphemy charges, against certain o’erly vocal members of the clergy: for the reader has but to glance about him, at the loathsome black tide of change, to which the atheistical Darwinists and their ilk have brought us!) Yet, even so, Dr. Hodge was not so adamantly conservative, and so opposed to all forms of “progress,” as to refuse to donate sums of money, to organizations of the scope, ambition, and daring, of the Sons of America Protective Association.

(This worthy organization, to which, I should here note, some two or three of my own ancestors belonged, was founded in 1889, out of a heroic response to the accelerated fear, on the part of the favored races, of being o’ercome by the swarthy tide, of the too prolific races,—the which, I need not sully my text, by here naming. Dr. Slade, Dr. Patton, Dr. Wilson, Dr. FitzRandolph, and many another concerned citizen, up to Mr. Roosevelt himself, and such custodians of our Republic’s well-being, as Mr. Vanderbilt, Mr. Rockefeller, Mr. Armour, Mr. Carnegie, Mr. Morgan, Mr. Hanna, and many more, too numerous here to list, thought it very unwise, to open the portals of Democracy, to such dangerous enemies of our tradition as Catholics,—of the southern climes of Europe, in particular—and Jews, and scarce-freed black slaves, and anarchists of every stripe: hence, the prompt assembling, in the 1880’s and ’90’s, of such altruistic and patriotic organizations, as the Daughters of the American Revolution, and the Sons of the American Revolution, and the Missionaries Alliance, and the American Patriots League, and Descendents of the Mayflower, and many another,—some, taking a general attitude of vigilance, against the incursions of barbaric change; others, addressing themselves to more specific, and even local, areas of suppuration, as Boston, with its flood of illiterate and superstitious Catholic immigrants; and California, gravely set upon by the “Oriental menace”; and the South, with its especial problem, of ignorant, uncouth, and animalistic blacks. The problem pertaining to Jewish infiltration, of near all areas of finance, trade, medicine, and even education, was deemed to be one afflicting urban and populous areas, primarily; yet no less grave, for that. Our University, I am pleased to say, under the guidance of Dr. Wilson, as of all the presidents, up to recent decades, solved the problem with very little fuss: which is to say, by behaving, with gentlemanly discretion, as if it did not exist!—it, and the proliferating tribe of Hebrew brethren themselves. As to Negroes, Woodrow Wilson was of the adamant belief that such personages should study in the South, in those especial institutions set aside for them; in his own well-chosen words, ’twas “altogether inadvisable for a colored man to enter Princeton,”—for the bookish clime alone should doubtless have proven disagreeable.)

That a goodly number of our Princeton families contributed funds to the Sons of America Protective Association, or to similar public-spirited societies, oft with a Protestant connection, argues, if any such argument be required, for their patriotism, and their abiding concern for American civilization,—albeit that, from time to time, in this history, we may chance to o’erhear them criticizing such leaders as Mr. Roosevelt. It was the great John Jay, a remote ancestor of the van Dijcks, who made the observation that “those who own the country ought to govern it”: by which the wise old Federalist meant, govern it well.

As to Dr. Palmer Fuerst’s lecture, “Rabies and Race,” I think it an indication of Josiah Slade’s tormented state of mind, that he should so suddenly recall the dread disease, in its hideous symptoms, yet forget entirely,—indeed, if he ever grasped—the challenging medical and scientific propositions, advanced by Dr. Fuerst and his colleagues in research!

This lecture was given, I believe, on the top floor of old Dickinson Hall, which at that time possessed the largest lecture-hall at the University; and it was fairly well attended, despite the infelicity of its scheduling,—mid-afternoon of the Friday of the Princeton-Yale football game, to be played in New Haven. In this limited space I cannot of course do justice to Dr. Fuerst’s eloquent presentation,—for which, I hope the reader will forgive me.

The substance of “Rabies and Race” here follows.

In late spring of 1895, it seems, in the impoverish’d hill community of Jellyby, Massachusetts, the sixteen-year-old son of a potato farmer, of no particular distinction, was stricken, of a sudden, with fever, and quickly grew so weak, he could not complete his day’s task in the field: but was brought home to bed. There, he suffered such hideous symptoms as frenzy, excessive salivation, spasmodic breath, violent headache, inability to speak coherently, inability to swallow either solids or liquids, and, not least, gradually accelerating terror, which threw the poor boy into convulsions. He soon slipped, mercifully, into a coma, from which he never woke: indeed, he died but forty-eight hours later’ leaving not only his astounded family, but all of Jellyby, o’ercome with grief and apprehension.

Jellyby being both remote and unenlightened,—its nearest “city,” some seventy-five miles to the south, is Pittsfield—there was a very strong likelihood, that this tragic instance might have been passed off, by an ignorant country doctor, as mere influenza or somesuch commonplace disease: but an alert county coroner, insisting upon an autopsy, sent his findings to a Boston laboratory,—whereupon it was discovered, that the boy had died of rabies.

Alas, rabies!—that most dreaded of disorders, about which so little was known, in 1895, and so much was feared!—for is any illness so cruel, so unremitting, so pitiless, and so cunning; does any illness known to man so challenge our faith in the Deity, and our confidence, that Jesus Christ is our ordained Savior, and that not even a sparrow falls, without the eye of God attending—?

(This heartfelt observation is but my own, and naught but incidental, for the distinguished Dr. Fuerst did not tarry in his lecture, wishing to dwell but briefly upon the particulars of the Jellyby case, and those to follow: for his intention, of course, was to put forth the essentials of his and his colleagues’ theory,—the which, being abstruse and challenging, and not aided, by the speaker’s monotony of delivery, offered some resistance to being comprehended, by an audience of undergraduates, and divers older members of the Princeton community, including some faculty members, and even a number of wives.

Yet I cannot resist an interpolation here, as to the cruelty and cunning, of that infamous disease, in which the reader too may take some small surprised interest. For, quite apart from the horror of its pathogenic assault, upon the frail human body, rabies can quietly reside in its unsuspecting,—nay, innocent—host, for nearly a year, betraying no symptoms!—whereupon, with maniacal suddenness, it springs to the fore, with headache, fever, nausea, tightening and convulsing of muscles, exacerbated nerves, anxiety, raving, hyperesthesia, epileptiform seizures, excruciating pain, that “foaming” at the mouth that is the consequence of uncontrollable salivation, and, alas, even more horrors: so torturing its victims, that madness oft o’ercomes them, and even the desire to bite; and death is certain. Indeed, in its more customary victims,—such warm-blooded creatures as dogs, cats, squirrels, rats, foxes, skunks, and even bats—rabies so possesses them with its own diabolical intent, to proliferate throughout the world, that they helplessly oblige the disease, by running mad, and biting other creatures. This has, of course, the necessary consequence, that the rabies virus is then communicated, by way of the infected saliva, to yet another hapless victim: and, from that, to yet another! And so, on and on, until all the victims are dead, or have been killed; or the entire world is rabid, and Rabies sovereign over all.

Was ever a disease so hideous, and yet so prescient?—so barbaric, yet proudly displaying certain indications, of a near-rational ingenuity? Young Josiah Slade must truly be pitied, for deeming himself rabid,and fit either to kill, or be killed: but we must question, whether this image of homicidal frenzy, is altogether appropriate, to a young gentleman of his moral courage, and familial heritage. More worthy is it, as a poetical designation, of being applied to such infuriated and witless creatures, as the Anarchists, and others of that foreign persuasion!)

The unfortunate case in northwestern Massachusetts soon came to the attention of Dr. Fuerst and his fellow scientists, at the Foundation’s headquarters in Cambridge: for these devoted gentlemen were, at that time, about to embark upon an experimental program of vast scope and ambition, springing out of Professor George Manley Beard’s masterly Degeneracy, Race, and Destiny, of 1891. (I had every intention of perusing Lord Beard’s famous study, which ran, I believe, into some five or six volumes, and presented quite a challenge, in its era, to the Socialists, Communists, and others of that “free-thinking” tribe, who sought to teach that material environment, and not inherited characteristics, determined mankind: yet this tome is now very hard to come by, and is not to be found, on either the open shelves, of the great Firestone Library at Princeton, or even in its hushed and regal Special Collections wing. The confus’d morass of elderly books, housed in Quatre Face,—this residence being, I should explain again, the ancestral home of the van Dijcks, many miles west of Princeton—is altogether innocent of Lord Beard’s volumes; and if they are to be found at Crosswicks Manse, in Dr. Slade’s old and cherished leatherbound library, they are, in any case, no longer accessible,—the property of the New Jersey Historical Society now, and zealously protected, by that vigilant institution.)

Dr. Fuerst and his teammates had not any particular interest, in precisely how the Jellyby rabies had been communicated: the testimony of the dead boy’s family, as to the probability of his having been infected, by a bite from a “drooling” barn cat, some three weeks previous, satisfied their curiosity. (They were, of course, greatly interested, to learn of any subsequent cases of rabies, in the vicinity: but, alas, none were reported.) Then, by one of those serendipitous events, that so frequently appear, in the annals of science and medicine, it happened that a young black boy, of twelve years of age, succumbed to the self-same lethal disease: this, within ninety days of the earlier case; yet, in a distant part of the state,—that ill-favored suburb of Boston, Roxbury.

This unfortunate child had been bitten, by the calculation of his elder brother, some eight months previous; and so withstood the onslaught of the dread virus, that, even once the actual horror of the rabid state had commenced, he held out for near nine days,—until he too lapsed into a coma, from which, alas, he never wakened. (He had, it seems, been infected, by a superficial bite, from a “very angry” stray dog, which had been subsequently shot to death, by someone in the neighborhood.) The Boston Foundation for Scientific Inquiries acted with alacrity, to commandeer the boy’s corpse, and to perform a careful autopsy: the somewhat o’erdetailed results being enumerated, in Dr. Fuerst’s lecture, yet proving too fatiguing, I believe, for the general ear; and far too Latinate, for my purposes. (I will content myself by observing only that the rabies virus is an obligate intracellular parasite; that it is neurotropic; that it cannot grow, or reproduce, outside the protoplasmic tissue of a living host; that the autopsy of the black boy yielded encephalomyelitis with Negri bodies, in central motor neurons,—the which, evidently, always means rabies.)

It was, I should make clear, not the Foundation’s research assignment to experiment with a rabies vaccine, along the lines so admirably, and ingeniously, set forth by Louis Pasteur and his associates, at the Ecole Normale, in Paris; in fact, Dr. Fuerst briefly alluded, with a chuckle, to an internecine rivalry of some sort, betwixt the Foundation, and a team of pathologists connected with the Massachusetts General Hospital, as to which group would first lay hands upon those unfortunates, of the Negroid race, who, over the next several years, were suspected of having contacted rabies. (There was, I gather, many an instance of competitive spirit, and some acts of bribery, and, most exciting of all, one or two actual races, by motorcar, in the wee hours of the morning!—an amiable rivalry that seems to have caused no permanent umbrage, betwixt the two teams of scientists, as the spoils were more or less evenly divided, in the long run.)

After the death of the twelve-year-old in Roxbury, there was a lull of some months, before another case presented itself: this, a forty-seven-year-old black woman, unemployed, residing in one of the most impoverish’d, and indecent, areas, in the city of Newark, New Jersey. (‘Twas a measure of the slovenliness of the victim’s way of life, that, whilst enjoying a lucid period, during the ravages of the disease, she could tell Dr. Fuerst and his colleagues naught of value,—having no clear notion of when she had been bitten, or by what creature!—as if bites by frenzied animals were but a commonplace of her life, and scarcely to be noted. Indeed, the victim’s reiterated plea, which grew very tiresome to the scientists, was simply that they save her life: or, failing that, put her out of her misery,—which tearful plea displayed a most remarkable “native wisdom,” as to the true gravity of her plight, in that the Foundation, the better to control the experiment, had informed the victim, and her family, that she had naught but a severe case of chickenpox, which they would cure forthwith.) This woman, of sturdy physique, and enjoying, it seems, fairly good health,—excepting, of course, the lethal contagion—quite amazed the gentlemen of science, by enduring some nine days, three hours, and forty-four minutes: for they held the normal span of endurance, based upon the Jellyby victim, to be a mere forty-eight hours. (By “normal” Dr. Fuerst meant, I assume, normal in a rabid victim of the white race.)

These findings were all most remarkable, yet, needless to say, very sketchy; for much more research was required, and a great quantity of hard data, before the Foundation would wish to set its findings before the world,—being, as it hardly needs amplification, an estimable organization, and not composed of scientists of the crank or “inspirational” school. Unfortunately, however, the single case of rabies that was reported, along the Atlantic seaboard, within the next month, was that of a gentleman of the Caucasian race: a well-to-do Wall Street attorney, in fact, who succumbed to a blazing fever not many hours after having been “brushed” in the face, whilst riding his steed in Central Park, by what he declared to have been a “large, soft, black-feathered bird,” but which was, doubtless, a rabid bat. This case was of course immediately referred to the crack team of rabies specialists, at Massachusetts General, who, employing a procedure very close to that of Pasteur’s,—involving some thirteen inoculations, of increasingly powerful vaccine, over a period of ten days—managed to save the gentleman: with the unlook’d-to result that, within eighteen days, he gave every appearance of being fully recovered!—and could not bestow enough praise, upon his physicians, and upon the world of modern science, in general.

This incident, by-the-by, occurred in late May, of 1897.

(Herewith, an amusing interruption: for, at this point in Dr. Fuerst’s solemn lecture, a husky bulldog waddled down one of the side aisles of the hall, and gave the learned gentleman quite a start! The redoubtable canine had been dozing beneath his master’s seat,—for, in those more companionable days at Princeton University, undergraduate men were allowed to keep dogs; and bulldogs were the breed most favored—when, for some undisclosed reason, he roused himself, and, unbeknownst to his young master, who was, I suspect, a-drowse as well, ventured out into the aisle, and made his way unhurriedly to the front of the stately old auditorium, where poor Dr. Fuerst was reading his lecture. I blush to imagine the scene!—which was most embarrassing, yet so amusing, that members of the audience who soon forgot what it was, the distinguished gentleman from Boston was presenting, on that afternoon, remembered all their lives the contretemps betwixt man and bulldog, in Dickinson Hall! For, as the fierce-brow’d creature approached the foot of the podium, he began most conspicuously to growl; and the lecturer, glancing up, failed at first to see who, or what, was making the sinister noise: which had the immediate consequence, of causing a ripple of laughter to flow through the assemblage. Again the dog growled; and, yet again, the hapless Dr. Fuerst, now grown pallid and strained, cast his eye about, with no luck. At last, the bulldog growling more stridently, Dr. Fuerst leaned over the podium, to gaze down o’er the tops of his glasses, and, seeing the creature, cried out for help, with a most comical expression of terror. [Did the credulous gentleman fear a rabid attack from such a friendly source, all wondered! Indeed, it was vastly entertaining,—and did not fail to stir laughter in even those administrators present, amongst them Dr. Patton himself.]

After some minutes of confusion, which had the felicitous effect, of awaking all who dozed in the warm hall, the proctors restored order; and the abashed undergraduate hurried forward, to take hold of his canine friend by the collar, and lead him away, whilst all the undergraduates in the room cheered and stamped their feet, and one reckless lad shouted out a request for a “locomotive salute,—to the dog,” which, I am relieved to say, was not pursued.)

The next incidence of rabies in a black specimen was not, unfortunately, for some months, which caused the Foundation no little frustration; and, when a case was reported, and brought to the Foundation’s attention, it was already too late,—for the impetuous rabies team, at Massachusetts General, reached the child first. (As to whether this small victim,—being a girl of but five years of age, bitten severely by a rat—survived the sequence of potent shots, Dr. Fuerst neglected to mention.) There then followed an initially promising instance, later in the year, involving a young black man in his twenties, bitten upward of a dozen times in the face and throat, by a maddened fox, in a wooded area in Hartford, Connecticut: this victim, the Foundation acquired with commendable alacrity, and placed in “polio” quarantine in Cambridge, but, as his case of rabies was so virulent, he died within thirty-six hours; and was diagnosed “atypical, in the Negro race.”

Thus, a good deal of precious time passed; and two or three additional victims appeared in the normal course of events; and the Foundation, grown impatient at last, arranged with officials at several prison facilities,—amongst them Mt. Horla State Penitentiary, in New Jersey; and the Providence State Asylum for the Criminally Insane, in Rhode Island; and Augustine State Prison, in Maine—whereby live rabies parasites might be injected directly into the bloodstreams of certain personages, deemed healthy specimens, of their kind, yet, withal, so far lost to all standards of human decency, that their loss, to the world, might be termed negligible. In this way, the “second phase” of the Foundation’s experimental program was launched, with gratifying results.

Herewith, Dr. Fuerst felt obliged to summarize; and to o’erburden his presentation, with numerous graphs, tables, statistics, and cumbersome Latinate words, which somewhat numbed his audience, and dulled the impact of his theory. Yet, the scientific principle here demonstrated,—as to the more primitive strength, of the darker races, to withstand physical stress—seemed incontestable: the more so, that the experiments had been undertaken with such especial probity, over a period of not less than eighteen months, and involving, in all, some eleven specimens. (These were Negro males, betwixt the ages of eighteen and fifty-seven, ranging in weight from one hundred ten pounds, to two hundred and seventy-five. Dr. Fuerst, in the published form of his lecture, included an addendum, which presented exhaustive data as to the ratio of weight, age, and physical type to the number of hours the dread disease was successfully withstood: this being,

—proffered here for the layman of scientific bent.)

That the swarthier-complected races of our globe, enjoying a closer proximity to their animal origins, than the Caucasians, are the better equipped to withstand such pestilent diseases as rabies, tetanus, syphilis, typhoid, malaria, tuberculosis, and many another; that the ordeal of childbirth, for the female, is never so arduous an experience, as it is for the white woman; that, in all, such primitive beings respond more instinctively, and with far less demonstrable physical suffering, to the vicissitudes of life, than their white counterparts,—these findings, the Foundation claimed, helped to substantiate the theories of pioneer researchers, foremost among them Lord Beard; and the more intuitive beliefs, of the general populace.

Thus, I have offered the substance of Dr. Fuerst’s public lecture at Princeton, of October 1898: a performance that must have disappointed somewhat, as, at its conclusion, near all of the assemblage departed, after but cursory applause. Young Josiah Slade, then a mere lad, albeit husky, of some eighteen years, made his way quickly out-of-doors; for he felt, he knew not why, fairly sickened in his heart; and had no query to put to the learned visitor. Only one undergraduate remained, with an o’er-particular question concerning Pasteur’s method; and a stooped and palsied emeritus professor, of the Faculty of Religion, with a querulous peroration, on the ancient curse laid upon the Sons of Ham.

* Or “suffragettes,” as they call themselves of late.

A major historical novel from “one of the great artistic forces of our time” (The Nation)—an eerie, unforgettable story of possession, power, and loss in early-twentieth-century Princeton, a cultural crossroads of the powerful and the damned.

A major historical novel from “one of the great artistic forces of our time” (The Nation)—an eerie, unforgettable story of possession, power, and loss in early-twentieth-century Princeton, a cultural crossroads of the powerful and the damned.

After some stressful minutes, as the young women made their way ever more deeply into a soft, sinking, bog-like part of the forest, into which Stony Brook Creek evidently emptied, at last they sighted Todd at the same moment, in a sort of clearing, in which gigantic logs lay in a jumbled profusion; the logs being ossified, it seemed, and formidable as fallen monuments. The sunshine that fell slantwise into this open space, having taken the peculiar quality of the great forest, did not seem, somehow, a natural sunshine, or the light of the sun itself, but rather a queer, silvery, lunar effulgence, unsettling yet not entirely disagreeable.

After some stressful minutes, as the young women made their way ever more deeply into a soft, sinking, bog-like part of the forest, into which Stony Brook Creek evidently emptied, at last they sighted Todd at the same moment, in a sort of clearing, in which gigantic logs lay in a jumbled profusion; the logs being ossified, it seemed, and formidable as fallen monuments. The sunshine that fell slantwise into this open space, having taken the peculiar quality of the great forest, did not seem, somehow, a natural sunshine, or the light of the sun itself, but rather a queer, silvery, lunar effulgence, unsettling yet not entirely disagreeable. And there was the German shepherd Thor so strangely stretched on the lichen-bed a few yards from the feet of the burning girl, muzzle extended, ears pricked into little triangles, eyes adoringly fixed upon the girl—why was Thor not barking but only just panting, audibly, as if he had run a great distance to throw himself down, as if in worship?

And there was the German shepherd Thor so strangely stretched on the lichen-bed a few yards from the feet of the burning girl, muzzle extended, ears pricked into little triangles, eyes adoringly fixed upon the girl—why was Thor not barking but only just panting, audibly, as if he had run a great distance to throw himself down, as if in worship?

Reviews

Reviews

I will definitely be reading The Accursed. Love Joyce Carol Oates’ writing.

LikeLike