Stories That Define Me

By Joyce Carol Oates Originally published in the New York Times Book Review, July 11, 1982. Telling stories, I discovered at the age of 3 or 4, is a way of […]

A Joyce Carol Oates Patchwork

By Joyce Carol Oates Originally published in the New York Times Book Review, July 11, 1982. Telling stories, I discovered at the age of 3 or 4, is a way of […]

Originally published in the New York Times Book Review, July 11, 1982.

Telling stories, I discovered at the age of 3 or 4, is a way of being told stories. One picture yields another; one set of words, another set of words. Like our dreams, the stories we tell are also the stories we are told. If I say that I write with the enormous hope of altering the world—and why write without that hope?—I should first say that I write to discover what it is I will have written. A love of reading stimulates the wish to write—so that one can read, as a reader, the words one has written. Storytellers may be finite in number but stories appear to be inexhaustible.

For many days—in fact for weeks—I have been tormented by the proposition that if I could set down, in reasonably lucid prose, the story of “the making of the writer Joyce Carol Oates,” I might in some rudimentary way be defined, at least to myself. Stretched upon a grammatical framework, who among us does not appear to make sense? But the story will not cohere. The necessary words will not arrange themselves. Of the 40-odd pages I have written (each, I should confess, with the rapt, naive certainty, At last I have it) very little strikes me as useful. The miniature stories I have told myself, by way of analyzing “myself,” are not precisely lies; but, since each contains so small a fraction of the truth, it is untrue. Text: Each angle of vision, each voice, yields (by way of that process of fictional abiogenesis all storytellers know) a separate writer-self, an alternative Joyce Carol Oates. Each miniature story exerts so powerful an appeal (to the author, that is) that it could, in time, evolve into a novel—for me the divine form, the ultimate artwork, toward which all the arts aspire. Consequently this “story” you are reading is an admission of failure, or, at the very most, a record of failed attempts. If knowing oneself is an alphabet, I seem to be stuck at A, and take solace from the elderly Yeats’s remark in a letter: “Man can embody truth but he cannot know it.”

One of the stories I tell myself has to do with the dream of a “sacred text.”

One of the stories I tell myself has to do with the dream of a “sacred text.”

Perhaps it is a dream, an actual dream: to set down words with such talismanic precision, such painstaking love, that they cannot be altered—that they constitute a reality of their own, and are not merely referential. It is one of the enigmas of our craft (so my writer friends agree) that, with the passage of time, how becomes an obsession, rather than what: It becomes increasingly more difficult to say the simplest things. Content yields to form, theme to “voice.” But we don’t know what voice is.

The story of the elusive sacred text has something to do with a childlike notion of omnipotent thoughts, a wish for immortality through language, a command that time stand still. What is curious is that writing, the act of writing, often satisfies these demands. We throw ourselves into it with such absorption, writing eight or 10 hours at a time, writing in our daydreams, composing in our sleep; we enter that fictional world so deeply that time seems to warp or to fold back in upon itself. Where do you find the time, people ask, to write so much? But the time I inhabit is protracted; my interior clock moves with frustrating slowness.

The melancholy secret at the heart of all creative activity (we are not talking here of quality, that ambiguous term) has something to do with our desire to complete a work and to perfect it—this very desire bringing with it our exclusion from that phase of our lives. Though a novel must be begun, often with extraordinary effort, it eventually acquires its own rhythm, its own voice, and begins to write itself; and when it is completed, the writer is expelled—the door closes slowly upon him or her, but it does close. A work of prose may be many things to many people, but to the author it is a monument to a certain chunk of time: so many pulsebeats, so much effort.

We were devising appropriate tombstone epitaphs for ourselves the other day, here in Princeton, where everyone is a writer though not invariably a reader (of the others, that is). “Out of Print,” we said, or “Gone into a New Edition,” or “Remaindered.” Perhaps “Shredded.” Afterward I thought of a cruel but apt epitaph for myself—”She Certainly Tried.”

Stories about Last Things always shade into uneasy laughter, a mask for terror, self-pity, nostalgia. So I should concentrate on First Things.

Those stories I told to myself, and eventually to others in the family, as a child were tirelessly executed in pictures, in pencil or crayon, because I couldn’t yet write. (I simulated handwriting at the bottom of pages, being eager to enter adulthood. Wasn’t handwriting what adults did?) My adult self, examining these aged and yellowed notebooks, judges the effort somewhat odd—the human and animal figures too detailed to be cartoon figures, yet not skillful enough to be drawings. The tablets were filled with these characters acting out complicated narratives—surprises, chase scenes, mistaken identities, happy endings—in the unconscious pursuit of (as I couldn’t have known then) the novel.

Eventually, at about the age of 5, like everyone else I learned to write. But it must be the case that the narrative impulse predates the wish for a sacred text, just as dreams are generally visual.

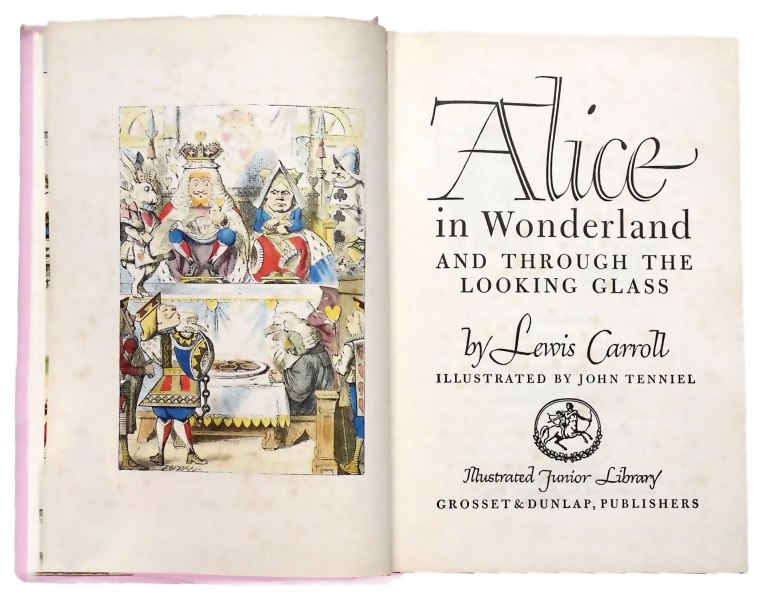

For some years my child-novels contained both drawings and prose, inspired, frequently, by the first great book of my life, the handsome 1946 edition of Grosset & Dunlap’s “Alice in Wonderland” and “Through the Looking Glass,” with the Tenniel illustrations. I might have wished to be Alice, that prototypical heroine of our race, but I knew myself too shy, too readily frightened of both the unknown and the known (Alice, never succumbing to terror, is not a real child), and too mischievous. Alice is a character in a story and must embody, throughout, a modicum of good manners and common sense. Though a child like me, she wasn’t telling her own story: That godly privilege resided with someone named, in gilt letters on the book’s spine, “Lewis Carroll.”

Being Lewis Carroll was infinitely more exciting than being Alice, so I became Lewis Carroll.

One part of Joyce Carol Oates lodges there—but to what degree, to what depth, I am unable to say. (How curious that 36 long years passed before I finally wrote a formal essay on Alice. But not on Alice; in fact, on Lewis Carroll.)

As for telling or writing stories, short stories in place of novels, I seem to have been unaware of the form until many years had passed and I had written several thousands of pages of prose (on tablets dutifully supplied by my parents, eventually on sheets of real paper by way of first a toy typewriter—marvelous zany invention—and then on a real typewriter, given to me at the age of 14). As a sophomore in high school, though my discovery had nothing to do with school, I accidentally opened a copy of Hemingway’s “In Our Time” in the public library one day and saw how chapters in an ongoing narrative might be self-contained units, both in the service of the larger structure and detachable, in a manner of speaking, from it. So I apprenticed myself, with my usual zeal, to this beautiful and elusive new form. I wrote several novels in imitation of Hemingway’s book, though not his prose style (that ironic burntout voice being merely monotonous to my adolescent ear), and eventually—though why it took so long I don’t know—I worked my way back to, or into, the short story as a prose work complete in itself.

It took me another decade to discover poetry. But then one is always discovering poetry for the first time.

One miniature story so frightened me, not only with its unanticipated content but with its icy ironic voice, that I had to abandon it within an hour. It begins:

“Precisely when I began to think of myself as posthumous, as a species of finely meshed, ceaselessly operating, unfailingly tuned clockwork mechanism composed of organic parts (infinitesimally tiny gears and pulleys, cogs and wheels the size of cells, wires the width of hairs), I should be able to say, with the intellectual’s grim elation at always knowing: but a strange oblivion washes over me and I remember too much, which is a way of remembering nothing. It might have been that devastating afternoon in the fall of 1956 when, as a freshman at Syracuse University, I was knocked to the floor of a basketball court by a player even more aggressive than I, and suffered, without knowing what it might be, without guessing what it might portend, the first, and very violent, tachycardiac seizure of my life: a breathless spasmodic fugue that allowed me to understand the proposition ‘All men are mortal’ in a way I hadn’t fully grasped in Logic 1A. On that day I lost my innocence, which I’ve never regained. On that day I comprehended a new concept of time. (Not a gently undulating stream bearing us all along, in the companionable drowse of our race, to whatever fitting destination—Posterity, The Void, Heaven / Purgatory / Hell—but a heartless, because entirely inhuman, current against which we must struggle, as if, at every second, swimming backward. Only in strenuous opposition to Time do we define ourselves: only in ceaseless—if futile—opposition to the biological current some call History do we transcend that current, and leave whatever it is our privilege to leave behind, to ‘outlive’ us. Giving up basketball forever—giving up, in fact, the combative physical life for more than a decade—I took on a more complex, more challenging game. I would not only continue to write as I had always done, discarding most of what I wrote (all this apprentice-work, thousands of pages of hopeful prose, more or less analogous to the musician’s constant practice at his instrument): I would transmute that process into an actual condition, a noun: I would become a writer. But I never regained my innocence. …”

The story breaks off at that point.

A “woman writer” is an anomalous thing, lacking a counterpart, a grammatical equivalent, a mate. For there are no “men writers.” Persons of either sex who write define themselves as writers, but roughly half of us are defined (by others) as women writers. Problems of a metaphysical as well as a practical nature arise.

When I began publishing stories and critical essays in the late 50’s, it seemed altogether natural for me to use the neutral name “J.C. Oates.” After I married and began with my customary blend of inspiration and pragmatism to revise my graduate seminar papers (in English—I received an M.A. at the University of Wisconsin), and to publish them in appropriate journals, I used the yet less melodic “J. Oates Smith.” Sometimes my professor-husband and I were published in the same journals, quite innocently, as fellow scholars, or even brothers.

For hadn’t I absorbed the unmistakable drift of certain prejudices, certain metaphysical / anatomical polarities? Even the otherwise egalitarian Thoreau, whose “Walden” I read at the age of 15 or 16 and have prized forever, even Thoreau, who understood that slavery is obscene because all men are equal, tells us matter-of-factly in “Reading” that there is a “memorable interval” between spoken and written languages. The first is transitory, a dialect merely, almost brutish, “and we learn it unconsciously, like the brutes, of our mothers.” The second is the mature language, the written language—”our father tongue, a reserved and select expression.”

One wonders: If brutes achieve a written language, are they no longer brutes? Or is their writing merely defined (by others) as brutish?

The above is a feminist story that does not raise its voice. It cannot, because I am not a radical feminist; I haven’t that innocence either.

My reasoning, unfashionable in some circles, shades into what is in another context a childhood story. For, as a child, in the company of other young children of both sexes, I was repeatedly—sometimes daily—tormented by older children (primarily, but not always exclusively, male), pursued across a field funnily called a “playground,” until my heart knocked against my ribs and I came close to collapsing. (Like my fellow first-, second-and third-graders at that one-room rural schoolhouse in Niagara County, six miles south of Lockport, N.Y., I learned to run fast at a tender age.) Once or twice I was singled out for not quite clinical molestation, less because I was female than because I was, at the moment, there. Also, it was said they liked my curly hair. Such systematic, tireless, sadistic persecution had the consequence of making me love with a passion the safe, even magical confines of home and schoolroom (cynosures of gentleness, affection, calm, sanity, books) and, later, library. For outside these magical confines the true brutes, or merely brutish Nature, await us.

But my feminism isn’t radical, or cannot at any rate automatically define the masculine as an enemy, since the cruelest persecutions at that rural schoolhouse were reserved for an older classmate of mine, a boy who wore glasses. Since he had weak eyes, it seemed logical that his particular punishment was to be rolled in dirt and dried leaves, so that his (weak) eyes might be injured.

So frequently attacked as a (woman) writer who writes about violence in the lives of fairly normal people, I recall the various nightmares of my childhood and tell myself that, after all, I did survive childhood and should not be especially pained at the violence of the critical attacks my writing receives. If pricked or even stabbed, I seem incapable lately of bleeding, but I am not invulnerable to psychic hurt—a fact I take to be a salutary sign.

A drunken peasant in czarist Russia is beating his overburdened, dying horse, a mare, and the child Raskolnikov and his father happen upon the scene. Raskolnikov wants to save the horse, but his father pulls him away, saying, as fathers have so frequently—so necessarily—said: It’s none of our business.

When I first read “Crime and Punishment” some time in my late teens, and came upon this image, it struck me as neither melodramatic nor lurid; nor was it, in its subtle configuration (child-witness, helpless “civilized” father, brutal “natural” peasant, female horse), anything other than a paradigmatic image, for me, of how the larger world—the world outside the home, the schoolroom, the library—is constituted. A melancholy vision, a “tragic” vision, but inevitable. Uplifting endings and resolutely cheery world views are appropriate to television commercials but insulting elsewhere. It is not only wicked to pretend otherwise, it is futile. If all a serious writer can hope to do is bear witness to such suffering, and to the experience of those lacking the means or the ability to express themselves, then he or she must bear witness, and not apologize for failing to entertain, or for “making nothing happen”—in Auden’s derisory phrase.

Scandal accrues to the many instances of madness and suicide in the profession of literature, but statistics tell us that other professions (among them dentistry, that least romantic of crafts) are more lethal. Scandal too arises over the notorious vanity and egotism of writers; yet I find my writer and poet friends the most unfailingly generous of people. The craft is certainly solitary, but the prevailing sense of life in literary America in our time is one of community. Male colleagues sometimes express envy of what they sense is a strong female (that is, feminist) community within that community, and they are justified in that envy. But while the craft is lonely the life assuredly is not.

As for our notorious egotism—Lear tells us the final truths about ourselves when he says of himself, “They lied when they told me I was everything.” These are hard, haunting words. They sift through my brain numberless times a day. Of course we are told we are everything, first by our parents, then by people who love us, or mean to encourage us; otherwise we couldn’t survive. Some of us require a boundless egotism if we are to have the spirit to write a single line, let alone a book. (Another book, Joyce! murmurs the abyss. And this, too, will alter the world?) But the artist must act upon the frail conviction that he is everything, else he will prove nothing. And as Lear has also warned us: “Nothing will come of nothing.” Hard, haunting words—our legacy.

Yes, genius, cannot be compared with any other writer. I’m grateful for every word she wrote.

LikeLike

Genius. Sheer genius. All I can say. This insight is highly appeciated.

LikeLike